THE YEARS BETWEEN THE GATES AND THE SPOTLIGHT

Freedom That Didn’t Feel Free

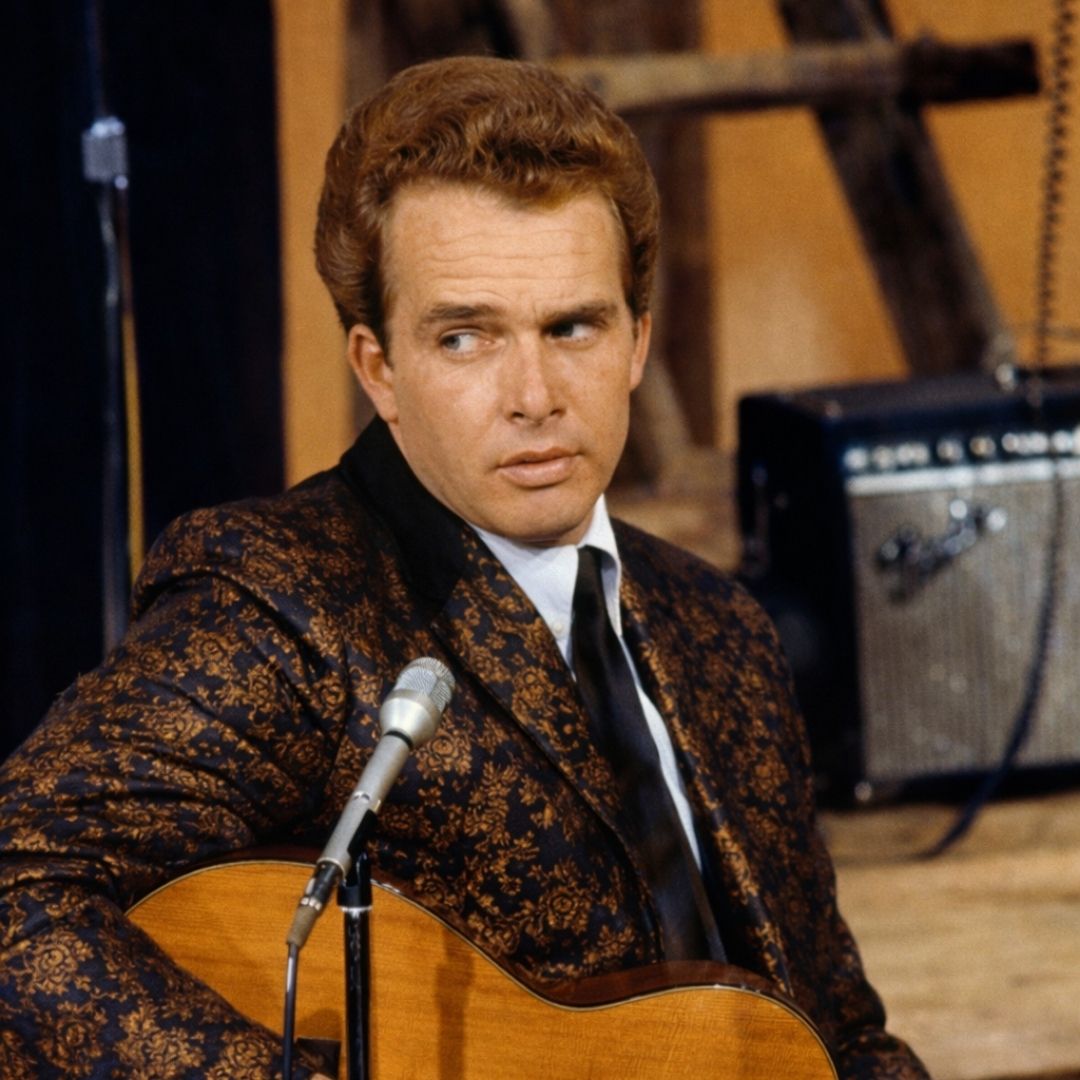

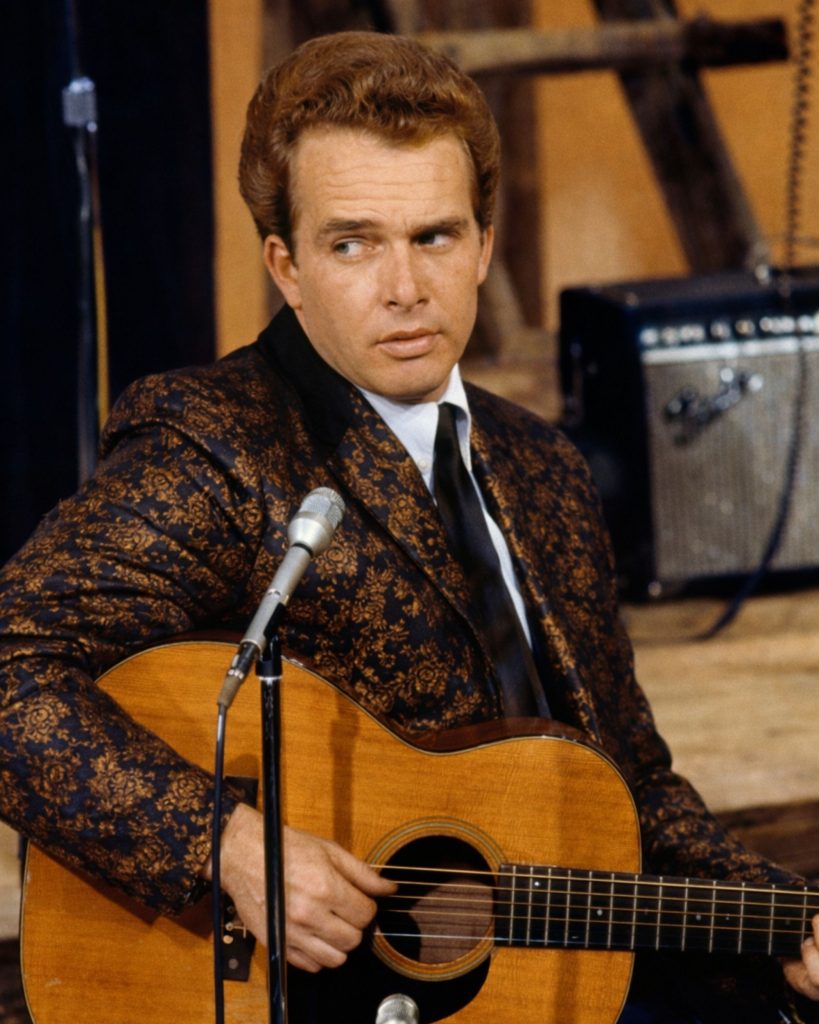

When Merle Haggard walked out of San Quentin in 1960, the world didn’t suddenly open up. Freedom came with conditions — parole rules, quiet judgment, and the invisible weight of a past that refused to stay behind prison walls. He found work, picked up his guitar again, and stepped into honky-tonks where some saw promise while others saw a man already defined by his mistakes.

Learning to Stand in His Own Story

Those early years weren’t about instant redemption. They were about survival — long nights on small stages, songs shaped by observation rather than confession. Merle didn’t rush to tell his story openly. Instead, he learned how to turn lived experience into music without turning himself into a cautionary tale. Every performance became practice in reclaiming identity.

The Song That Said What He Wouldn’t

When “Branded Man” arrived, it didn’t sound like apology. It sounded like recognition. The lyrics carried the reality of someone marked by history yet refusing to disappear behind it. Listeners heard honesty without self-pity — a balance that made the song resonate beyond biography.

Turning Stigma Into Strength

Seven years after leaving prison, watching the song climb to No. 1 felt like more than chart success. It marked a shift in how audiences saw him — not as a man escaping his past, but as someone reshaping it. The album Branded Man reaching the top confirmed that his story, once seen as limitation, had become connection.

What the Charts Couldn’t Show

Between prison bars and the first No. 1 lived countless quiet decisions: choosing work over relapse, music over silence, authenticity over reinvention. Merle Haggard didn’t erase the brand society gave him; he turned it into identity. And in doing so, he proved that sometimes the path to the spotlight isn’t about leaving the past behind — it’s about learning how to walk forward with it.