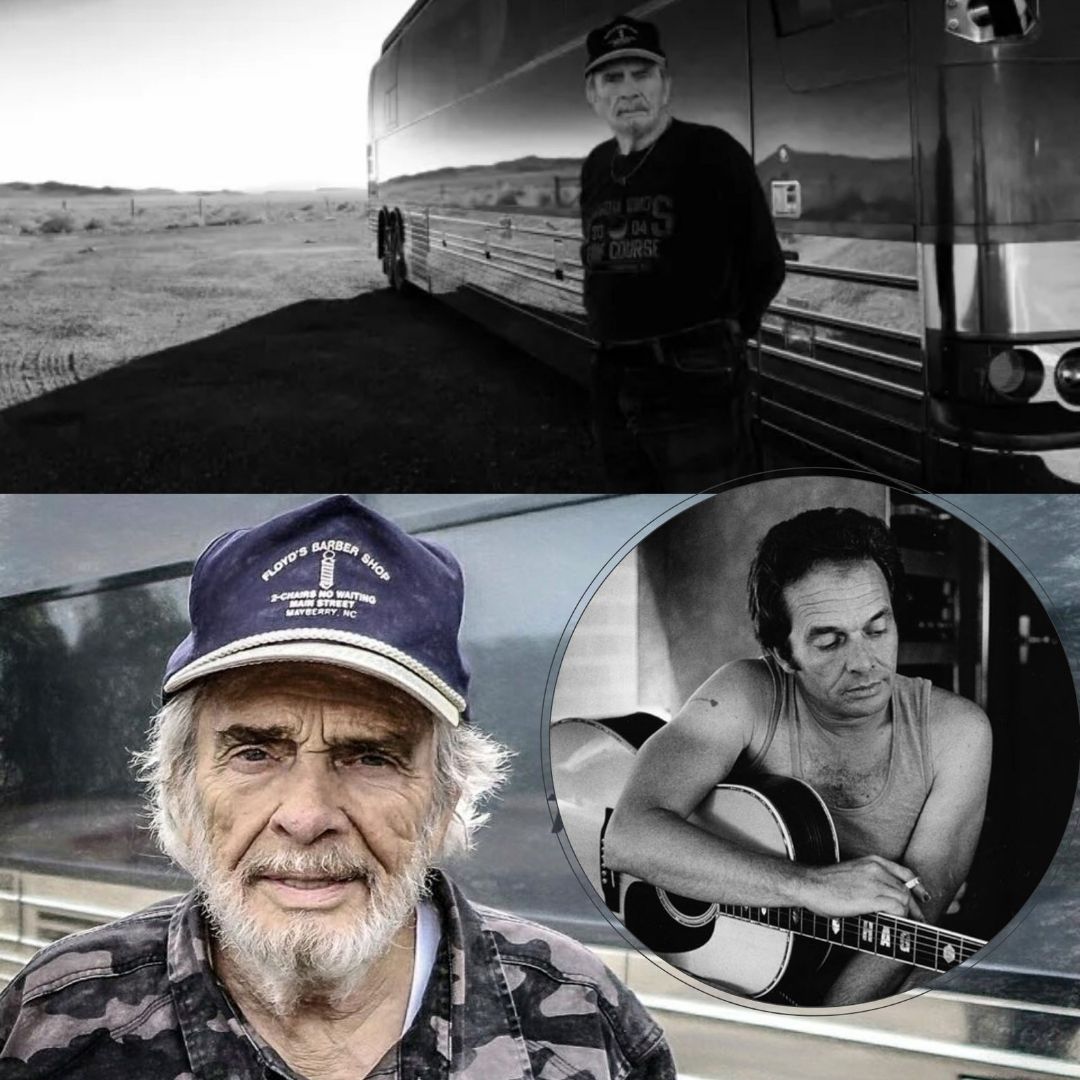

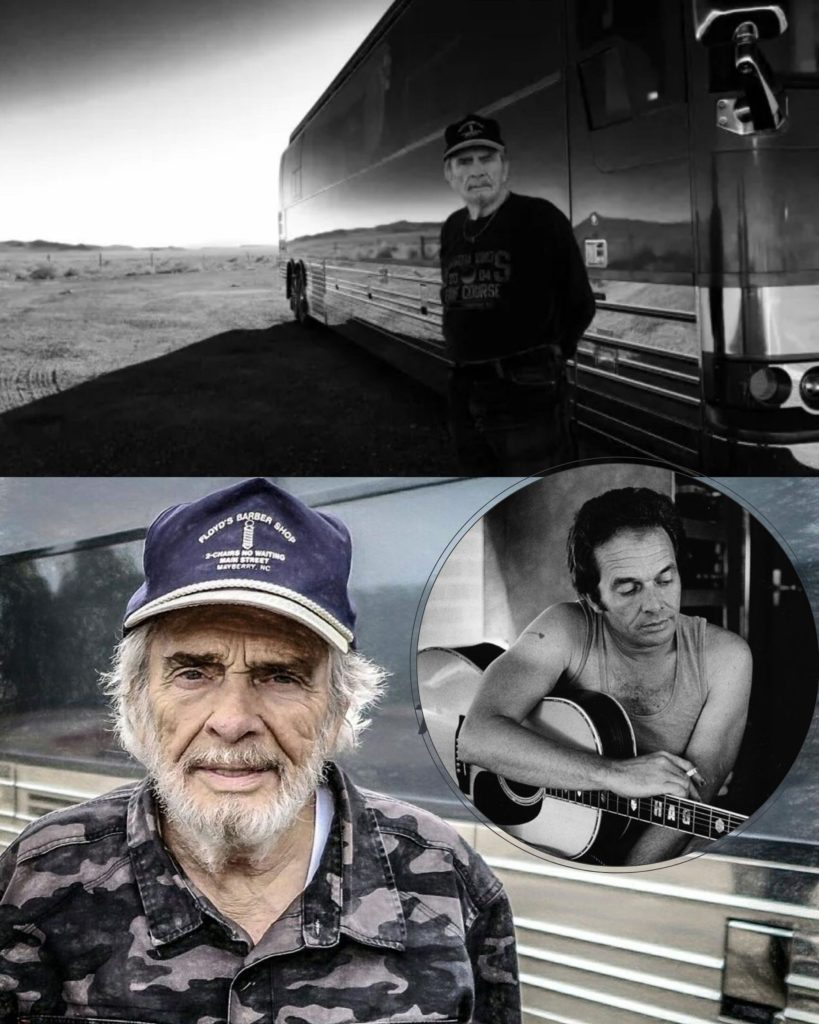

It all began with a day off in Northern California while on tour with Marty Stuart. Marty, ever the instigator of memorable moments, woke the crew early, announcing, “Hag’s picking us up.” That “Hag” was none other than Merle Haggard himself, pulling up in a white pickup-style Cadillac Escalade, dressed more like a West Coast rapper than a country legend—a flat-brimmed hat, a camo overcoat, and the unmistakable aura of a man who’d seen everything. “He looked like a Bakersfield gangster,” Scruggs recalls, laughing.

Haggard drove them out to his home in Palo Cedro—a modest house once owned by Fuzzy Owen, his longtime manager and steel player. The contrast between the simplicity of the home and the enormity of Haggard’s influence in music was striking. On the property, landscapers were planting young redwood trees. Haggard, a bit irked at the price—$1,700 per tree—nonetheless seemed invested in the act. “It reminded me of the Buddhist saying about planting trees you’ll never sit under,” Scruggs says, recognizing the poetic truth: Haggard was planting for a future he wouldn’t live to see. It was just a year before his death.

The heart of the story, however, unfolds with music. Inside the home, Haggard handed Scruggs one of the most storied instruments in country history: Lefty Frizzell’s Bigsby-neck Gibson J-200. This was the very guitar Haggard had first strummed on stage as a teenager, urged on by Frizzell himself. The moment was symbolic, cyclical—history folding in on itself. Scruggs strummed an E chord, and Haggard began to sing Long Black Veil, slipping into a Lefty-inspired drawl that could melt time.

As the verses passed between them, Scruggs caught a glimpse of the “deep waters” in Haggard’s eyes—still and calm, but never shallow. “He had that energy about him,” Scruggs says. “Even when he smiled, you weren’t sure if he was happy or dangerous. That poker face—like a guy who’d been to prison and learned never to give anything away.”

They played more songs, including on Haggard’s own custom Fender Telecaster, and shared stories, joints, laughter, and biscuits and gravy. On the coffee table: a fiddle case. Inside? Bob Wills’ fiddle—another relic of the roots that shaped Haggard’s world.

Chris Scruggs’ day with Merle Haggard wasn’t just a hang—it was a passing of torches, guitars, and truths. And maybe that’s the essence of country music itself: a humble room, a sacred instrument, and a soul who knew the weight of a lyric.

Video